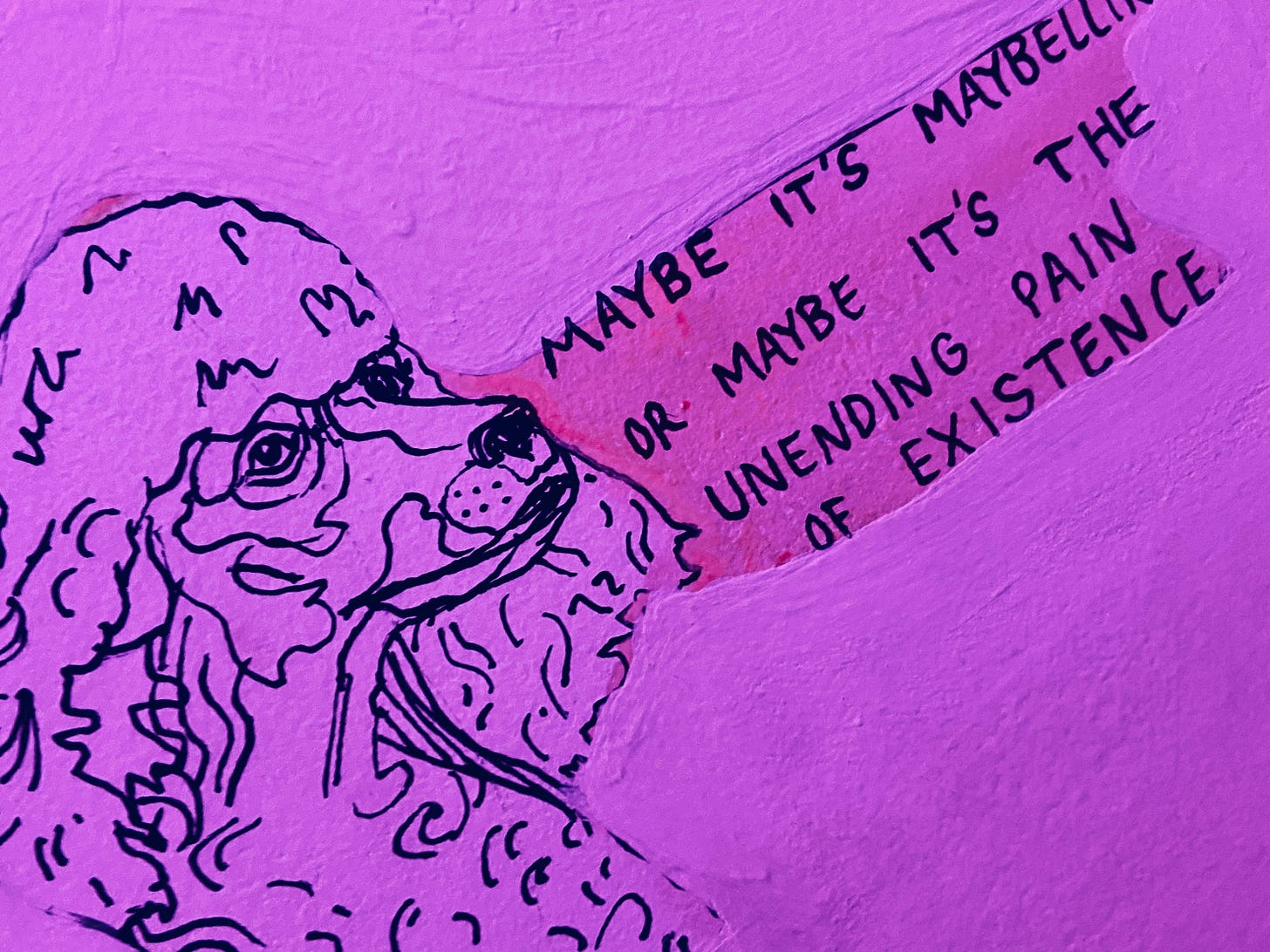

Something I hear frequently relative to my job is some version of “that must be so hard.” It’s a logical conclusion, and it’s true—it is a hard job.

In the emotional realm, I encounter grief, sorrow, and fear on a daily basis. I meet many people who appear poorly equipped to navigate their reality, who are facing profound remorse, and who are coming to the end without a feeling of satisfaction, resolution, or reconciliation. No one wants to die feeling like a loser at game of life, but it is very common.

The physical challenges stem from being on my feet a lot. I sometimes find myself in awkward postures, like offering reiki in a weird position to accommodate tubing, linens, or equipment, or I may find myself bent at an odd angle to offer a prayer or anointing. There is a high degree of exposure to unknown pathogens, frequent donning and doffing of PPE, and I engage with dozens of people every day.

Mentally it can be difficult to know how to reach people; I rely heavily on intuition and my familiarity with psychology to try and find a way to connect. Lots of people desperately want and need companionship, but have lived such emotionally isolated lives they have no idea how to let someone know them. There is A LOT to know about religion, which comes up less than you might think, but I do feel a sense of obligation to be at least somewhat well informed in this regard. There is also navigating the system of the hospital, with its politics and regulations.

Yes, my job is challenging in myriad ways. But the thing is: I don’t want an easy job. The prayer of my life, to whatever power exists, is, “Use me.” I don’t perceive my life is solely my own. Rather, that my work is to become as much myself as possible, so I can find the niche that I’m meant, uniquely, to fill.

I have learned that I am the kind of person who wants to be wholeheartedly engaged, and in that way, chaplaincy (and writing!) is perfect for me. Believe it or not, being a chaplain is far easier for me than marketing or project management, which I found existentially unsatisfying and thus nearly impossible. My effort to excel in either role left me feeling like a failure—I never cared enough to fully apply myself.

As I am beginning to get my feet under me in this vocation, I am beginning to reach some conclusions about the disposition of a chaplain. One quality I am certain is required may seem quite obvious. It is WILLINGNESS.

To be a good chaplain, you have to be willing to do the work, to witness pain of all kinds, and to endanger yourself. You have to be willing to operate in a gray area—to not know the answers, and to continue learning. You have to be willing to advocate in a system that often doesn’t care, and to maintain hope when there are infinite reasons to give up.

Another thing that is required to be a good chaplain is ENDURANCE. You must endure the suffering of others. You must endure inequity and injustice of all kinds. Most of all, you must find a way to endure the constant stream of patients (which leads to a constant stream of work). One of my first epiphanies when I started residency was how the rooms kept filling up; patients just kept coming. The need for medical care—the demand—is inexhaustible.

(This is to say nothing of the need for health care.)

Willingness and endurance are two qualities that separate a professional chaplain from a layperson. However, all of us are called to serve a similar role at one time or another. No one is spared heartache and loss, and all of us have mortal bodies. More critically, we live in communities, be they large or small, intimate or distant. This all but guarantees that, sooner or later, life will invite us to fulfill the role of a chaplain for our loved ones—that is, to companion them through their suffering. How can you do that well?

Here are a few ideas to help you feel more comfortable and perhaps even skillful at meeting others in their suffering.

1. Listen for the feelings.

It can be so tempting to problem solve when a person expresses a hardship or heartbreak. But problem solving when someone is in deep emotional pain is isolating for the person who is suffering. If you want to help them, join them.

What might you say to a friend going through a breakup or divorce? I know a great attorney might *seem* useful, but if they’re in their feeling body, it will not land. When someone is in their feelings, meet them there, and save practical matters for another time.

I never liked him for you is also not likely to land well. Instead of feeling your support, they’ll feel judged.

Think back to a break up in your own life. How did you feel? Sad, lost, abandoned, rejected, dislocated…these are the feelings your friend is likely having. So say something related, like:

I can imagine you’re feeling rejected; that is such a painful feeling

After all the time you spent together I wonder if it feels like you don’t know how to be without them?

I remember feeling anxious and afraid of the future when I got divorced…maybe you feel similarly?

You can also simply say something like, “It sounds like you’re really sad. What else are you feeling?” This demonstrates your care and interest as well as your willingness to accompany them through their experience—an invaluable offering to a person going through a hard time.

2. State the obvious.

Say a friend’s dog was hit by a car and died. You might be tempted to point out the obvious and suggest they can get another dog. This is not what I mean about stating the obvious! Such a sentiment may give you a moment of relief from their pain, but it will probably feel to them like you don’t understand their experience. Their suffering is not about the absence of a dog in their life. It’s about losing their beloved friend and family member. Instead say:

This is horrible

It’s so upsetting to imagine they were in pain

Nothing will ever replace him/her, and that is such a sad thing to consider

You might be afraid to state the obvious for fear of planting an idea in their head, but believe me: unless they’re in shock or denial, they’re already thinking what you’re thinking (and then some).

You saying what is so has a dual purpose. It will affirm reality, which their emotional body is trying to reconcile. This is especially important when someone is in shock or denial. Naming what is true (with tenderness and care) will also validate their experience and demonstrate they aren’t alone.

Whether it’s a pet death, discovery of cheating, a new diagnosis, amputation of a limb, etc., the immediate work of the care recipient is coming to terms with reality. Your presence and compassion at such a time will help them ground so they can begin to process their new reality.

3. Be curious.

I often meet with people who have been told there is nothing more that can be done to treat their condition. They may have days, weeks, or months, but one way or another, their disease process is going to end their life, typically before the person is ready.

Well. What can you possibly say to someone facing their untimely death, who is helpless to stop it?

I certainly don’t bring up memory making or bucket lists at this point…that is a conversation to have once they’ve come to terms with their revised reality. Instead, I get curious:

I wonder what it is like for you to know your death is imminent… (wondering questions are to a chaplain what a hammer is to a carpenter)

Did you ever imagine you’d reach a time like this in your life?

What thoughts do you find yourself returning to, if you’re willing to share them?

The point is not to get to any clear answer but to invite the person into reflection and to facilitate meaningful conversation. It is not uncommon at all to encounter people who know they are dying and are surrounded by loved ones who nonetheless have no one to talk to about it. People don’t like to talk about death or suffering. If you want to be useful to someone having a hard time, be willing to go there with them, and be curious.

Offer gentleness.

I mentioned wondering questions, and gentleness is one of my favorite things about this approach. It allows the care provider to join the care recipient in a way that demonstrates both compassion and curiosity while also gently focusing the discussion.

Also, through your wondering, you give the person to whom you’re providing care an opportunity to compare the wondering that you expressed against their own experience. This will help refine their understanding of themselves, which moves them in the direction of their own answers or solutions.

Recently I met a young woman who was diagnosed with liver failure. She was not a candidate for a transplant because she hadn’t been sober for six months, which is required to be added to the waiting list. Her doctors didn’t think she would make it that long, and even if she did, six months of sobriety would only get her on the list. Who knew how long she would have to wait before a suitable organ would be found?

This meant she was likely to die, but even that was uncertain. She was young, and younger bodies tend to fare better in pretty much every outcome related to illness and injury. There might have been a chance she’d make it, but that would require an extraordinary amount of work on her part, at a time when she was really down and out. (It’s amazing that life often asks the most of us when we’re the least resourced.)

Alcoholism is a difficult thing to tend for many reasons, but perhaps most of all because people who struggle with that disease blame themselves for it. As I sat with the patient, I thought through what she might be feeling (blame) and addressed it directly, but gently.

“Alcoholism is tricky…a lot of people blame themselves for it. And that just compounds the pain that people are generally drinking to numb.”

She looked me in the eyes for the first time when I said that, and we were able to have a conversation about how awful her early life had been. I told her I understood why she drank, and said how unfair it was that she didn’t have the parents she needed and deserved. This was more kindness/compassion/gentleness than she could quite accept due to her deep self criticism, which may have originated in her assuming responsibility as a child for the shortcomings of adults.

Clearly, that pattern wasn’t going to be fixed in a day. But at least in that moment she got to feel acceptance—the opposite of judgement—and perhaps a glimmer of the softness life had denied her.

Other things you can say to convey gentleness:

I am here with you, and I will stay as long as you need to feel some relief from these hard emotions

I don’t know the right thing to say, but I want you to know I care a lot about what is happening in your life

This is really hard…I’ll stay with you while we find a way forward that you feel okay with

I truly believe that we can handle whatever life throws at us if we don’t have to do it alone. As you sit with the person to whom you’re offering care, know that your mere presence is healing and profoundly helpful.

Be quiet and bring your full attention.

Chaplaincy is sometimes referred to as a ministry of presence, and it’s often true that the most valuable thing I offer a care recipient is evidence that they matter. I do this by 1) showing up, and 2) paying attention.

Early in my training, one of my educators challenged me around this. He said, “Try and do a visit in which you don’t ask a single question.”

Some time the same week he suggested it, I visited an early 30’s man who was hospitalized with indistinct but serious symptoms after finding his also thirty-something wife dead on their living room couch. They didn’t know why she died, which I learned as I listened to him go on and on about her death, her life, and what it all meant for him. I sat with him for more than an hour, and I didn’t ask a single question.

Abandoning inquiry of my own, I had to sit with the horror he described. Every time my mind wandered to a question, I tried to turn back to his voice, sentiments, and concerns. It was a difficult visit. But as I prepared to leave he said, “Thank you for letting me say all of that. I haven’t been able to talk about this with anyone and felt like it was rotting my insides.”

My presence and attention was all he needed to begin healing. He was discharged the next day.

The power of presence is never more evident than with patients who are conscious but cannot speak. I generally start these visits by sitting down and introducing myself. I tell the person that I know they can’t respond in words, but that I will try and hear them through their eye contact, or by squeezing my hand. I tell them about the weather, and the day. I might summarize very generally what I know about their condition (e.g. “I understand you were having trouble breathing…that’s why the ventilator is helping you breathe right now…so you can get stronger.”)

It would be impossible to convey the depth I have seen in the eyes of patients who can’t tell me a single thing, who know they are sick, who have no one else to sit with them in stillness. I will ask if it’s okay to smooth their hair, which seems a universal comfort. Their eyes will tell me yes or no. I can tell I have earned their trust when they close their eyes and let me tend to them, slowly tracing lines on their forehead or massaging their scalp gently with my fingertips. What a profound thing to share with a stranger; I am certain these exchanges offer me as much as I am offering them.

People over perfection.

When an occasion arises in which you’re called to care for someone in pain, I hope you will let go of any attachment to doing it right. I still say the wrong thing sometimes, for example walking into a patient’s room on the oncology floor and saying something like, “Hi there…how are you?”

I mean, duh. Every time I hear myself say something so thoughtless, my next sentiment is something like, “You know, I’m so sorry. That’s not what I meant to say. I meant to acknowledge that you’re in the hospital, which is often unpleasant. In light of that, how are you feeling?”

Often, the person will smile or give a nod of understanding at my faux pas. Obviously, I’m trying to connect, and they appreciate the effort. Since I just broke the ice and demonstrated vulnerability, it opens up the space for us to meet in our common humanity, and we go on to share a moment, or several.

That you’ve read this far shows your desire to be of service to the people you love. That willingness to endure with them is all it really takes.